Karma is not your boyfriend

Why believing 'good things happen to good people' can be disastrous

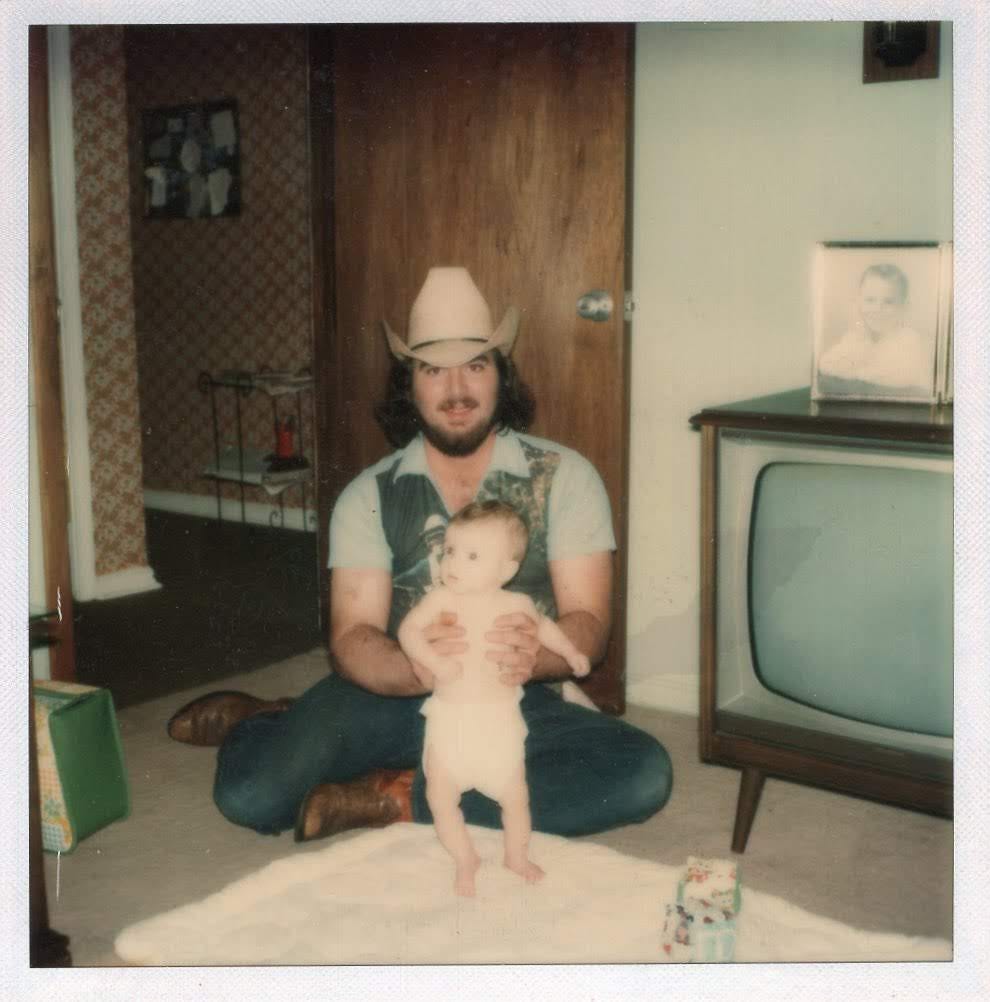

When I was a kid, a man shot my uncle in the head at close range. He didn’t know the assailant, but he had gotten into a brief verbal altercation with him at a bar earlier in the evening.

Did my uncle deserve to be shot?

You’re probably answering of course not, he didn’t deserve it. That’s crazy! And then you might start thinking…wait, is there more I don’t know? What was said during this brief altercation? Did he give this random man a reason to raise a gun and fire?

See what just happened there? You’re suddenly looking for reasons. Many of us do this reflexively, even when we know it’s not helpful or kind. It stems from the presumption that good things happen to good people, and that bad (or stupid, or careless) people eventually get punished.

It’s such a common way of thinking that there’s a name for it. Psychologists call it the “just-world bias,” which is the belief that the world is predictable, orderly, and fair. It’s akin to karma, if we’re using that word in the simplified way Taylor Swift uses it in her song by the same name.

Reap what you sow, aka victim-blame

In spite of copious evidence otherwise (see: the Middle East, all mass shootings, famine, false convictions, etc), many of us hold onto belief that “we reap what we sow.” It’s a coping mechanism, fostered in us since youth. “Our positive beliefs help us to function and live happily in a world that can often be downright frightening,” writes David B. Feldman, PhD, a professor of counseling psychology at Santa Clara University.

That’s useful — except when it goes too far. As research shows, when something inexplicable happens, humans will invent reasons to explain it, usually focusing on the victim’s actions. And once we cobble together those reasons, we think we are safe from harm, because we’ve figured it all out.

“The problem is that it sacrifices another person’s well-being for our own. It overlooks the reality that perpetrators are to blame for acts of crime and violence, not victims,” Feldman notes.

AKA, victim-blaming. Perhaps no sentence better exemplifies this then the classic “What was she wearing?”

For many of us, it’s too terrifying to realize it doesn’t matter.

Self-blame is hard to overcome

If you’re a trauma victim, this leads to isolation. You may be dealing with hypervigilance and nightmares as a result of a terrifying event, and then on top of that, “everybody else is still walking around wanting to believe bad things don't happen,” explains Emily Hurst, PhD, a clinical psychology doctoral candidate at University of Detroit Mercy who is seeking middle-aged people for her research on how extreme stress affects ways of thinking.

But there’s also your own internal core beliefs telling you the same thing: That you’re somehow culpable in your own suffering. Hurst told me that even when her trauma patients learn about the just-world bias, they still struggle with self-blame.

“Because we teach people that good people get good things and bad people get bad things,” she says. “That’s in storybooks. It's on TV shows. It's in religion. Just over time, that's how you think. Everything resolves in a movie. Everything resolves in a TV show. Everything resolves in life.”

“Until we really have something that forces us to think about some of these core beliefs critically, a lot of times we don't know we have them. That’s the issue with having to redo them,” she says.

Developing your own belief system

Eventually, and usually with help, someone can heal from trauma and reshape their core beliefs. In some ways, that can be a gift. Not a gift anyone ever wants to deal with, of course, but it does mean deeper self-awareness and empathy for others, or as Feldman puts in his book, becoming a supersurvivor.

You can let go of the just-world bias and begin to move toward something more akin to secular humanism, in which you know anything can happen at any time, and that you don’t inherently deserve anything from the universe, yet you strive to be a compassionate and just person regardless.

Because I sure as hell don’t have any better ideas on how to muddle through life, I do think trying to be “good” is probably a noble goal. But I definitely don’t think I deserve anything from a higher power for my good actions. Maybe karma is a cat, as TSwift says, but that cat can scratch.

Shout-out to Marika Páez Wiesen, author of Living the In-Between Times, for the subject line inspiration.